Description:

In April, 1969, former Oklahoma City mayor George Shirk, his sister, and two friends entered an unobtrusive door on the side of a condemned building at 12 S. Robinson. Leaving daylight and the bustle and noise of downtown traffic behind, they descended into Oklahoma City legend.

Work was scheduled to begin soon on a major urban renewal project, the Myriad Convention Center, and Shirk had been tipped off that beneath the rows of condemned buildings along South Robinson a subterranean chamber had been discovered. Armed with flashlights and old-fashioned Okie intrepidity, the quartet explored a vast subterranean chamber which appeared to be the legendary underground Chinese city that Oklahoma Cityans had always heard about, but no one seemed to remember ever having actually seen. For decades parents kept their children in check by telling them if they didn’t behave the Chinese would take them into the tunnels and they’d disappear; generations of high school pranksters tried to locate the underground city; and even distinguished professors from Norman came up to document the phenomenon, but no one could ever find a way in – if it existed at all.

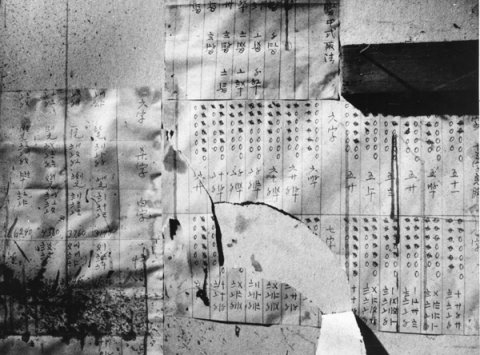

But the Shirk expedition found a way in and discovered large community rooms 25 feet wide with passageways leading to 4x6 foot sleeping chambers. A kitchen area was found with an intact stove. They also found Chinese writing all over the walls including one sign near a sturdy door with a window in it. No one present spoke Chinese, but it was later translated by a restaurant employee who said it read “Come Gamble”. It was not recorded how far below the surface they explored, but they did discover two levels below the buildings’ basement level, so the underground city was quite deep.

As soon as the discovery was reported in the Daily Oklahoman, long-time residents rose up and submitted their own anecdotes. Several people who had lived in the rooming houses in the area said they remembered that Chinese people always lived in the basement apartments and could access their underground areas from there. Some remembered the Chinese growing bean sprouts and mushrooms underground. One former neighbor recalled that one day the Chinese were simply gone – that was around 1948. One former resident, bookseller James Neill Northe, had befriended some of his Chinese neighbors and he recalled that he was invited in as the last Chinese were leaving. He saw Fan Tan (a Chinese gambling game) markers and a Buddhist temple. Another man who had been a landlord in the area was told that there was a third level which contained a Buddhist temple and a burial area. Shirk’s expedition did not find this third level.

To most of us the idea of a Chinese city underground (or any city underground) is quite exotic. However, placed in the proper context, it really isn’t surprising at all that such a place existed. Chinese immigration to America began with the California Gold Rush in 1848. Life in China had become chaotic after its forced ‘opening’ to Western trade caused the corrupt and repressive Manchu dynasty to collapse. Like nearly every other immigrant group coming to America, the Chinese were lured by the promise of a better life; thousands came seeking fortune, but few achieved it. It was in the 1850’s as planning and implementation of the Trans-Continental Railroad began that hundreds of thousands of Chinese began to flow through San Francisco into the inter-mountain west. Because building the railroad would be labor intensive, the line builders needed a huge workforce and the Chinese quickly filled that role. Life was hard for these workers and because they were often temperamentally meek and hard-working, they were willing to do almost any job and consequently did not gain the respect of broader American society.

Vast differences in European-based and Chinese cultures only worsened relations between the two societies. Nearly everything about Chinese culture was unusual to the European residents of the West. The Chinese language emphasized inflection and tone, there was no alphabet and the writing did not progress from left-to-right as in most European languages. These only made assimilation more difficult. There were other things as well such as the strangeness (to Europeans) of the Buddhist religion, ancestor worship, and, because of the high value placed on luck in Chinese culture, an almost fanatical obsession with gambling. These factors not only prevented the Chinese from assimilating easily, but also slowed the cultural commerce (trading ideas, language, and foods, etc.) between the mainstream and immigrant societies. The Chinese banded together like most immigrant societies, but because the differences were so great this only served to alienate them and make them seem sinister or at best untrustworthy to mainstream society.

There was another, darker, side to the cultural differences which were often used, hypocritically, to attack Chinese culture in America. Officials in western towns often pointed to the Chinese propensity for gambling, but also prostitution and the opium trade as detrimental to society and local police forces made life very difficult for what were often legitimate Chinese business owners. It was true that prostitution and opium were a problem in western Chinatowns. However, one must consider that until the Twentieth Century the west was known as the Wild West and was inhabited largely by young unmarried males who often had normal human desires and lots of money; but taking into account that the ratio of Chinese men to women around 1870 was 700,000 to 4,000 one can see that prostitution in Chinatown was no worse than it was for society at large. It was also true that opium addiction had long been a problem in China (prompting two wars with Britain) and those addictions did travel with the immigrants. But again, without condoning drug abuse, it’s important to understand that the lives of these people were so miserable that they sought relief in the numbing effects of opium. And, when put into perspective, it was no more a scourge than alcoholism had become for American society at large.

By the 1880’s the railroads had been built and the huge Chinese labor force was no longer needed. Chinese workers began to move into farming and manufacturing work. All the while, thousands of Chinese immigrants continued to stream into San Francisco – two million by 1880. Leaders in Western states began to fear that the Chinese would take the jobs of already established workers, so they began a campaign to limit or stop Chinese immigration. The result was the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 which stopped virtually all Chinese immigration. To make matters worse, all Chinese who were caught in the United States without proper ‘paperwork’ (which was virtually all of them) would be immediately deported. There were other similar laws enacted such as an act which forbade Chinese men from marrying Caucasian women.

All of these factors served to literally drive most Chinese communities underground because of the dangers of living amid mainstream society. The Chinese lived under most cities in the west with San Francisco obviously having the most developed underground network. Many other places from Seattle to Moose Jaw to Boise had underground cities, and Deadwood, South Dakota has even made a tourist attraction of their existing underground city. So, although it’s still exotic, it’s no surprise that Oklahoma City had an underground city as well.

No one knows for sure, but the first Chinese immigrant probably came to Oklahoma City with the construction of the railroad or at the time of the Land Run. We do know that when the first city directory was published in 1890, there were five Chinese listed (Sam Chong, Hong Kee, Ming Lee, Sing Lee, and Wah Hop). These enterprising men most likely had come to the United States before the Exclusion Act and had been able to secure resident status. It is safe to assume that there were more than just these five Chinese in the city. However, later census records for 1900, 1910, and 1920 consistently list only a handful of Chinese in Oklahoma City.

As important as the Shirk expedition was, its discovery merely serves to confirm for later generations that such a place existed – it was unable to really illustrate for us what life was like inside the subterranean town. Few non-Chinese ever ventured into the catacombs, but we do have some records of people who did. In 1921 the Oklahoma Department of Health began a campaign to improve sanitation and living conditions in the state’s boarding houses, restaurants, grocery stores and the like. So in January, state health inspectors swarmed over eighty locations in Oklahoma City – six inspectors and one sheriff went underground. The inspectors were doubly amazed when they entered the subterranean village via a blue door in the alley off Robinson between Grand (Sheridan) and California – they did not expect the underground area to be so extensive nor did they expect it to be so clean. The inspectors found several caverns of sleeping rooms extending from a central living room and kitchen and they reported that all the passageways were expertly dug and quite securely designed. Apparently two men shared a hollowed out room with dirt walls and floor and slept on grass mats placed on the floor. There were enough of these rooms to house an estimated 200 people. One inspector reported that the area seemed well-suited for three things – sleeping, eating, and gambling. Inspectors assured the Chinese inside that they weren’t concerned with gambling, just safety, and went about their business. At first they had assumed there were only two levels, but when they were all-too-eagerly greeted by men at the far end of the system, they realized there must’ve been a third level below which allowed someone to run ahead and alert the other residents. Finally, despite a raised eyebrow over the crate of live chickens in the kitchen, the inspectors confiscated two dirty blankets and gave the entire community a glowing, clean bill of health. By contrast, several above-ground restaurants and rooming houses were cited or closed down due to poor sanitation.

The fascinating thing about the inspectors’ report is that it confirms much of the ‘archaeological’ evidence unearthed by the Shirk expedition as well as the anecdotes shared by longtime Oklahoma City residents. The report also suggests that conditions in Oklahoma City’s Chinatown were much milder than that of other, larger cities in the west. The inspectors were accompanied by a policeman and none in attendance seemed overly concerned about either the level of gambling or the presence of opium dens (the inspectors apparently did not see any of the tell-tale signs of opium use).

Because these hard-working early citizens kept to themselves, we know very little about their personal lives. The one we know the most about, though, is Willie Hong, known variously as “The Mayor of Chinatown”, “Uncle Willie”, or “The Librarian”. Willie Hong was born in China and made his way to San Francisco’s Chinatown as a young man before moving to Oklahoma City around 1918. Hong’s main occupation was as a local agent for San Francisco companies that supplied Chinese restaurants around the nation. But Uncle Willie quickly came to represent his countrymen as well. While most laundrymen and restaurant workers would simply smile and pretend ignorance of English, Willie was always the one who would speak for the estimated 100 Chinese living under South Robinson.

Hong was quite a learned man and operated a Chinese library at 210 West California for over twenty years. Chinese herbalist manuals and the writings of Confucius shared shelf space with the World Almanac and English-language newspapers. Besides acting as the local secretary for the Kuo Min Tang – the Chinese Nationalist Party, Hong was also the de facto representative for all things Chinese in the city. When the local schools learned about China, there was Willie to talk to the students; if a newspaper reporter needed a local angle on a story about China, he talked to Willie; and when a local organization had an international night, Willie represented China. Uncle Willie also acted as liaison for many of his countrymen. One area landlord recalls that whenever any Chinese got “into trouble”, Willie always fixed things and he also made the rounds every month and made sure everyone paid their rent. James Neill Northe remembered that during the Depression Hong ran a doughnut shop called Uncle Willie’s and his offer of two doughnuts and a cup of coffee for only a nickel was relief to many in those days.

After Japan invaded China in 1937, Willie Hong became quite active in raising funds for relief efforts in China. After learning that his niece had been killed and the library had burned in the bombing of his hometown he felt a personal responsibility to aid in the relief efforts, so he earned a degree in physiotherapy and waited until war’s end to go back to China and assist in emergency medical work there. We can’t be sure what happened to him after that, although we do know that the Kuo Min Tang became involved in the struggle against Mao Tse Tung’s Communist Party for control of China – a struggle the Maoists eventually won.

Sometime shortly after World War II, the underground Chinese colony was abandoned. No one is really sure why. The Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943, and even though the Act was loosely and infrequently enforced in Oklahoma, its repeal erased any doubt that the Chinese were now able to live freely above ground and take part in the society of which most of them had spent the majority of their lives on the fringe. Many of them may have gone back to China to fight in the civil war while others simply wove their lives into the fabric of Oklahoma City life. The various urban renewal projects in the area have probably removed any physical evidence of the old Chinese city, but there are still underground passages in Oklahoma City. Some believe the tunnels that once connected the many movie theatres on Main Street and allowed runners to shuttle film reels back and forth are still intact. Of course we still have the Conncourse, the ambitious underground system of passages connecting several major buildings downtown. And there’s still a Chinese restaurant underground – the China Chef in the Conncourse.