Description:

Oklahoma City is home to a diverse mix of cultures and ethnicities: Native American, African-American, Czech, Irish, Polish, to name a few. But it is the Hispanic culture that has had a major influence on South Oklahoma City.

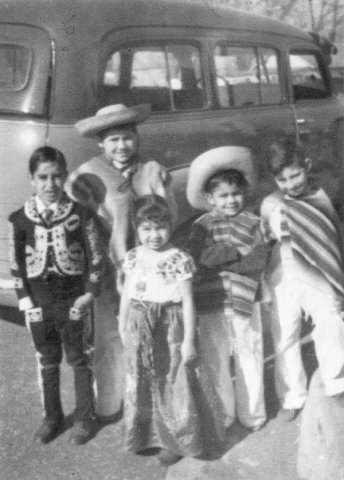

Influential in the state since earliest recorded history, much of Oklahoma’s Western heritage has its origins in Hispanic culture. Early-day cowboy dress was influenced by the Mexican cattle industry: sombreros, leather chaps, and the lariat can all be traced back directly to the Spanish Southwest. Hispanic place names are abundant all over the state of Oklahoma: Carmen, Carrizo, Gallienas, Hidalgo, Peno, and Plano, for example. The celebration of Cinco de Mayo, a popular annual event in many Oklahoma cities, marks the victory of the Mexican Army over the French at the Battle of Puebla, which took place in May of 1862.

Spanish-speaking conquistadors were the first non-indigenous group to explore the region, coming with Coronado in 1541. Later, Spanish miners working the Wichita Mountains were among the early settlers. After about 1910, people of Mexican ancestry began to come to Oklahoma in an effort to escape from poverty and violent revolutions sweeping across Mexico. They were drawn to the area by the promise of employment on railroad section gangs; Oklahoma railroads were known to pay higher wages than other states in an effort to keep their Mexican workers, and many immigrants were able to find employment with the Atchison, Topeka , and Santa Fe and M-K-T railroads during the heyday of Oklahoma railroad construction. Others came to work in the coal mines of eastern Oklahoma, or to obtain seasonal jobs during the cotton harvests.

The social and religious center of the Mexican community in Oklahoma City is Little Flower Church, located on South Walker Street. In 1921, the Order of Discalced Carmelites received permission to establish a mission for the purpose of ministering to the growing Catholic population in Oklahoma’s capital city. Despite being menaced by the Ku Klux Klan, the Carmelites were able to build a structure, completing Little Flower in 1927. Included was a school for children, a clinic, and a community house. A beautiful facility, the Little Flower Church was instrumental in providing educational opportunities for Mexican families, offering classes taught both in English and Spanish. Sermons and religious ceremonies, as well as other social functions, took place in Spanish.

As in Mexico, the primary focus of an immigrant’s life in Oklahoma was the family. Patriarchal in nature, the family provided solidarity and comfort in surroundings that were often unfamiliar and hostile. Many families were able to keep their Hispanic character and nature, speaking Spanish in the home and refusing to give up their special heritage.

The role of women was limited to the home: it was considered demeaning for a man’s wife or daughters to work outside the home, no matter how impoverished the family might be. Children were taught a great respect for their parents -- especially their fathers -- and to take responsibility for their siblings as well as their elders.

Most Hispanic families were Catholic. First communions, confirmations, and weddings provided the opportunity to relax and celebrate in the Catholic tradition. Fiestas were also held in honor of Saint’s days and feast days. Women would gather to cook delicious foods such as tortillas, menudo, tamales, enchiladas, chiles rellenos, flautas, tacos, and more. Many of these foods have become common dishes in Oklahoma City and throughout the nation.

When the United States entered into World War II, the opportunity arose for Oklahoma Mexicans and their American-born children to improve their status and quality of life. A huge demand for wartime labor forced industries to open their doors to all types of workers, regardless of their sex or ethnic backgrounds. Many became naturalized citizens by serving in the armed forces.

In fact, Mexican-Americans were the nation’s most highly decorated ethnic minority during World War II. The story of Manual Perez, Jr., is a particularly riveting one. He was a member of the United States Army, Company A, 511th Infantry, 11th Airborne Division. Using his own rifle, bayonet, grenades, and the rifle of a Japanese soldier he’d killed in hand-to-hand combat, Perez was able to save his entire company from danger by single-handedly killing 18 enemy soldiers. Before he was informed that he’d won the Medal of Honor, Perez was killed by a Japanese sniper. He was laid to rest in Oklahoma City.

Another heroic feat was accomplished some 33 years earlier by Rufino Rodriguez, a 22-year-old miner working in a coal mine near Lehigh, Oklahoma. He saved 190 of his fellow workers when a fire broke out near the bottom of a mine shaft. Rodriguez fought through the maze of suffocating smoke to sound the alarm, to alert other miners, and to help others who were struggling to safety. After falling unconscious near the main entry, he was pulled to safety. For his bravery, Rodriguez received a bronze medal from the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission.

With the end of World War II, the Hispanic community in Oklahoma City expectantly looked forward to greater opportunities than had ever been available before. Mexican-American veterans qualified for the G.I. Bill, making it easier to acquire a college education. Others were able to receive on-the-job training or obtain loans to start their own businesses and to purchase homes.

Cultural pride, a continuing flow of Hispanic-American immigrants, and a strong ethnic tradition are what binds together the Hispanic community in Oklahoma City. Key to Oklahoma from the very beginning, the Hispanic culture is part of what makes Oklahoma City so special and unique.

RESOURCES

Calhoun, Sharon Cooper. Oklahoma Adventure. Oklahoma City, OK: ACP, Inc. 2000.

Lambert, Paul F. Historic Oklahoma: An Illustrated History. San Antonio, TX: Historical Publishing Network. 2000.

Smith, Michael M. The Mexicans in Oklahoma. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. 1980.

Wagoner, Jay J. Oklahoma! Oklahoma City, OK: Thunderbird Books. 1994.

FURTHER READING

Fernandez-Shaw, Carlos M. The Hispanic Presence in North America. New York: Facts on File. 1991.

Gonzales, Juan. Harvest of Empire: A History of Latinos in America. New York: Viking. 2000.

Griffith, Terry L. Oklahoma City: statehood to 1930. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub. 2000.

Griffith, Terry L. Oklahoma City: 1930 to the Millennium. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub. 2000.

Latrobe, Charles Joseph. The rambler in Oklahoma: Latrobe’s tour with Washington Irving. Oklahoma City: Harlow Publishing Corp. 1955.

Oklahoma: the first hundred years. Ada, OK: Galaxy Publications. 1988.